Environmental Economics, Part I

This class is taught by the very awesome Harold Levrel, who likes to welcome us back from breaks with little quizzes on animals. He very rightly pointed out that even most people steeped in environmental issues don't always know how to recognized the birds, plants and creatures around us {side note: this is sometimes called plant neglect and there's been some scary studies about how the average kid can recognize way more Pokémon that living things...}

History of Environmental Economics

Economics is the the optimal management of scarce resources, and environmental economics is the sum of interactions between humans and our environment. It's basically about survival, how we organize ourselves around the material we need to reproduce our societies. There's a ton of ways to do this — capitalism works through private property and salaried labor and markets — but the ones we prefer are trading, bartering, gifting and returning favors, and all the other alternative ways to share our resources.

In the Pleistocene (which started 2.5 million years ago and went till 11,700 years ago, also known as the Ice Age brrrrrr) humans were part of the food chain, as both predator and prey. Collective organizing and alliances (with wolves for example) for hunts, which varied seasonally along with the berries, nuts, and plants gathered. They already were using exosomatic tools {exosomatic is a fancy word that means outside of the body, endosomatic is part of our body — so hands are endosomatic tools, hammers are exosomatic} and if they ran out of food, they moved to a different spot. They used fires to move herds of prey into ravines, and likely hunted a bunch of big animals to extinction, since the arrival of humans onto the continents now known as the Americas and Australia coincides with mass disappearances of ancient elephant-like gomphotheres (though a warming climate might have also been a factor, archeologists are pretty much currently in agreement that humans where the key accelerator of their demise, though the cool thing with archaeology is that new sites are found all the time that constantly update our timelines and understandings of all this!)

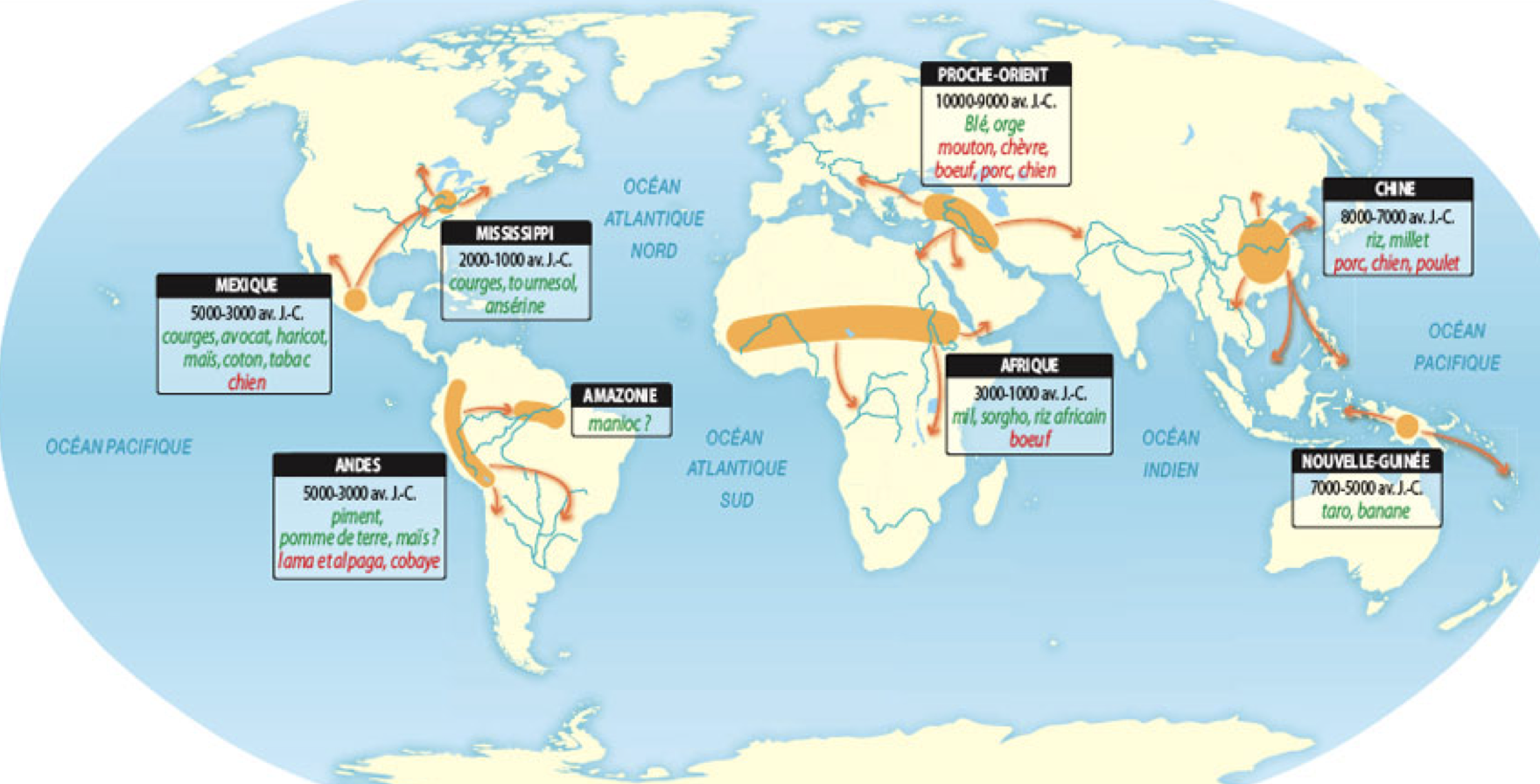

In Neolithic times, our ancestors get started on horticulture, encouraging the growth of some edible plants in forests, and figuring out how to plant stuff in fertile river beds after seasonal floods (hence the Fertile Crescent.) They also start domesticating animals (or more likely, they domesticated themselves) and we slowly started getting ourselves off the food chain. We start making stuff (pottery! clothes! weapons!) and exchanging stuff. There's probably some notion of shared ownership given that people want to reap what they sow, and have some guarantee that the effort put in bears fruit. It's debated that domestication followed the decline and extinction of megafauna, as a way to get meat without having to go super far, which would make it the first adaptation to a planetary limit. Adapting allows us to control variability in the environment, and irrigation to augment soil fertility looks like it starts around then too. This happened simultaneously all over the world with different plants and animals, usually around rivers, coasts and estuaries. Also, boats! Cool invention. And proto-currencies like shells. These experiments in sedentarisation make reserves logical, since they can help tide over shortage spells during winters to avoid having to migrate.

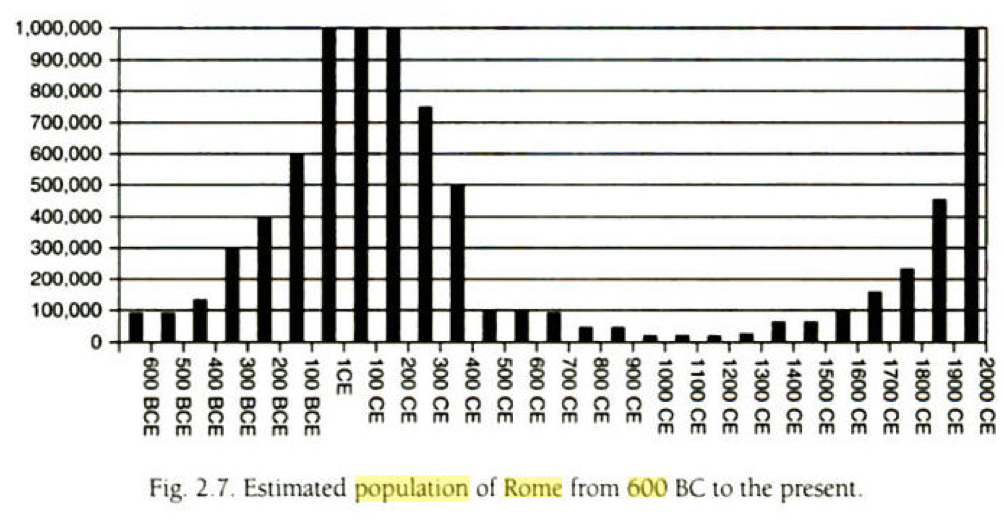

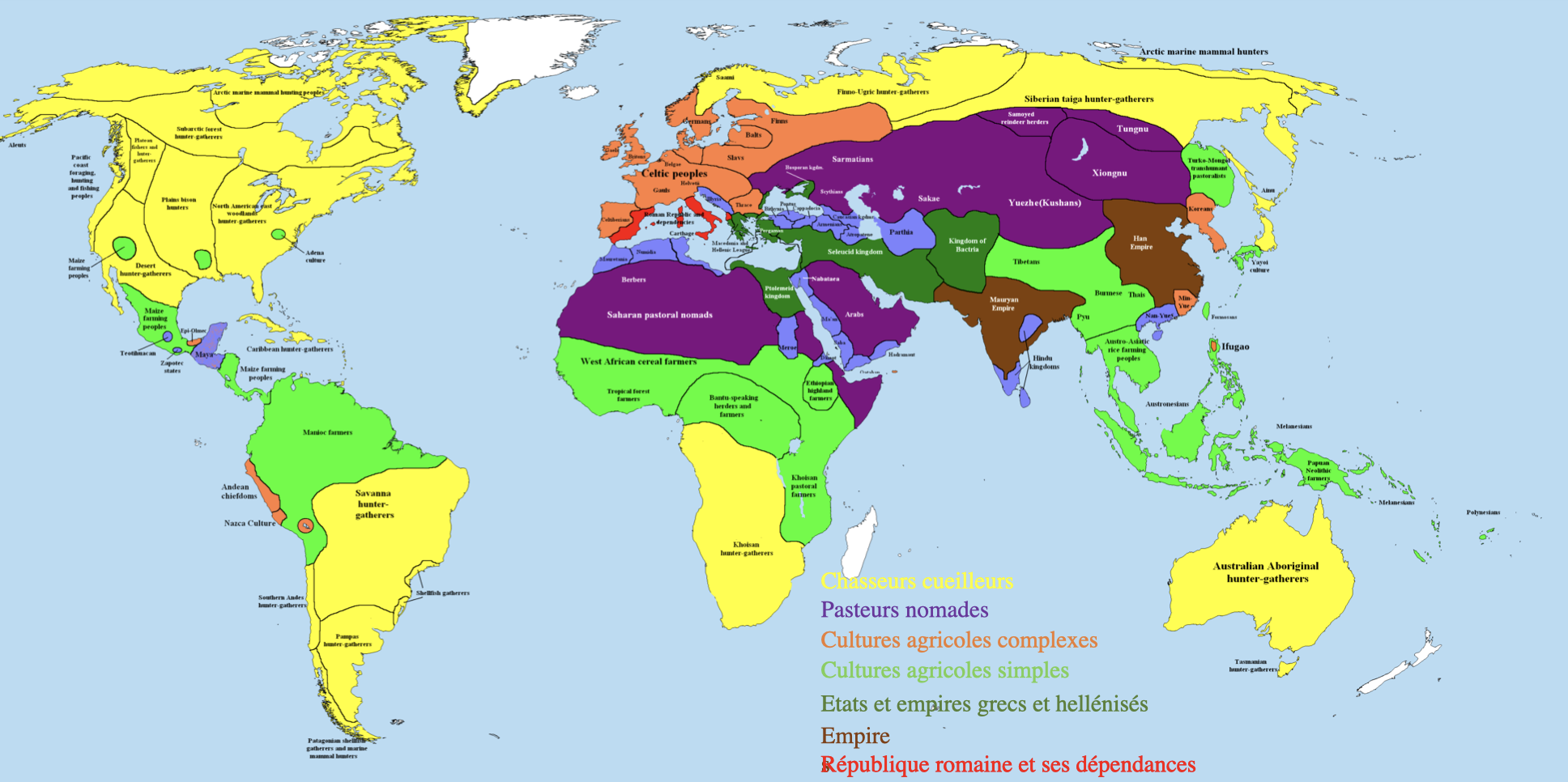

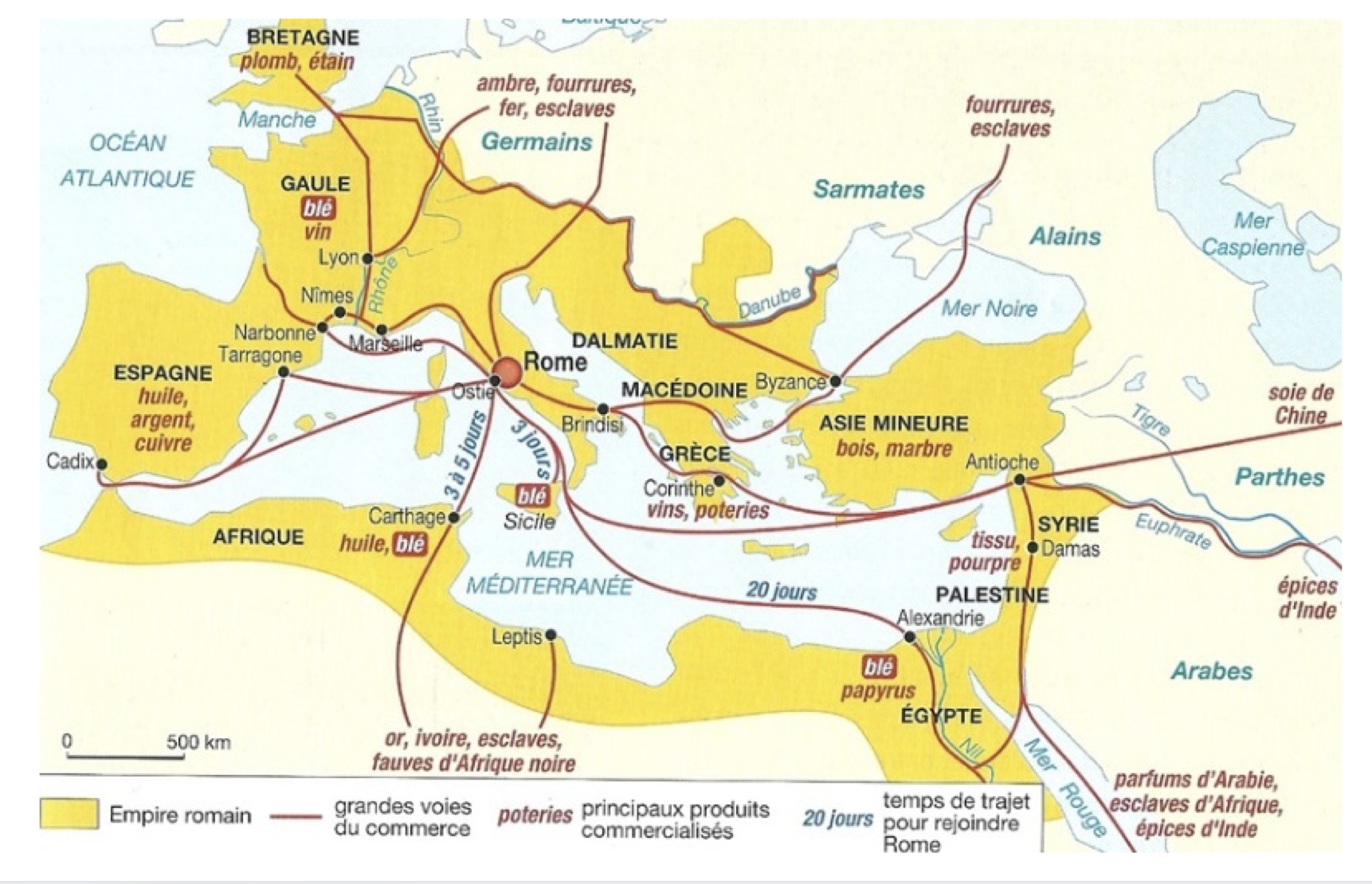

By 200 BCE, we're got religions - shared beliefs amongst distant peoples - and Rome has one million people. Cities of that scale won't come back for another 20 centuries, so this is pretty huge. Globalization is really kicking off, we're getting super specialized regions making just one thing (olives) and we've got roads and sea routes to move all that stuff around.

Empires start minting coins and giving themselves a monopoly on violence to administering armies/cops to levy taxes. The economy gets itself out of a direct link to the environment, and you don't really need to know or care how things got from A to B or who made them out of what and when, as long as you have enough coins to get a widget at the market. Social classes start to stratify, and we get philosophy (yay) and philosopher Xenophon names Oikos {home} Nomos {management} aka economics aka home ec. Relatedly, the word ecology from the name root, and it means home knowledge <3.

From the get go, Aristotle marks the difference between finance (the science of money, and making money for money's sake, amoral usury, wasteful decadence etc etc) and economics (managing means.) This gets us back to the key notion of capacity, and the inherent limits to our ecosystems. If we fuck around with our home management oikos nomos, we find out we're out of a home. Bad management leads to crisis and collapses of all kinds, often in the form of diminishing returns like when you deforest all of your empire to make cereal fields until you can't feed your growing empire. Then people get mad at the emperor, especially if he's behaving ostentatiously and conspicuously consuming lavish ridiculousness. Plus there was a heat wave that led to more desertification in North Africa, and the endless conquests to enslave more people and grab more resources was getting more and more costly. Also, no new technology miraculously appeared to save them. And speaking of, I'm at 8% battery and it's late, so we'll get to feodal times later.